- Starting your Research

- Finding Sources

- Primary and Secondary Sources

- Scholarly, Trade or Popular Periodicals

- Evaluating Sources

- Citing Sources

- Plagiarism

The Research Process

Research is a complicated process and can be intimidating when you haven't had much experience with it. It's a little easier to manage if you follow these steps:

It's important to remember that the research process doesn't always go smoothly. You may have to go back and refine or change your topic or search strategies as you work. You might discover that your ideas about a topic were wrong. You might end up finding the resources you selected aren't appropriate and have to try again. That's ok! Those are all parts of the research process.

Getting Organized

Before you start your research you might want to get a reference manager like Zotero or Mendeley. Both are free programs that store information about the books, journal articles, websites, and other information sources you'll use. With Zotero or Mendeley, you can annotate your sources, create citations in any style, and create bibliographies quickly and easily.

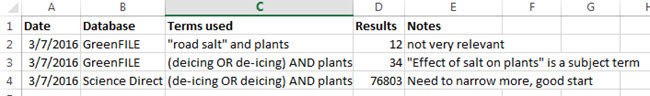

You might also want to consider keeping a research log. You can use a research log to record search terms, databases, results, and anything else you think might be helpful. Keeping track of your research will help you improve your searches by showing you the most effective terms and databases for your topic. It will also prevent you from repeating searches you've already tried. You can make a research log in whatever format you prefer. Here's an example:

Picking a Topic

Picking a good research topic can be a challenge! There are no rules for choosing a topic or developing a thesis, but the following approach may help:

Start by listing subjects that are appropriate to the assignment and that interest you. If you're stuck, think about ideas you've discussed in class, current events, things you may have heard on the radio, or ask your professor for help. At this stage, you should be thinking in nouns. For example:

- reality television

- human cloning

- Captain Ahab

Next, make some claims about your topic by adding verbs. These might not end up being true, and that's ok.

- Reality television is therapeutic for viewers

- Human cloning is more likely to damage than enhance human life

- Captain Ahab should be understood as a tragic hero

You now have potential thesis statements. The thesis—a claim to be proved or disproved by factual evidence and persuasive argument—is what drives most research. Once you've decided on a thesis, begin researching it as a question:

- Is reality television more than entertainment?

- What are the most likely consequences of human cloning?

- Can Ahab be understood as heroic?

Creating a Search Strategy

Once you're ready to start searching, it's time to create a search strategy. Being thoughtful at this stage will save you time in the future. Make a list of keywords that have to do with your subject. Be sure to think about other ways to phrase your topic. The specific words you search for matter. If you're not seeing enough results, or not seeing the right results, you might have better luck searching for synonyms or related words.

This part can be challenging if you don't know much about your topic yet. If you're having trouble thinking of words or phrases related to your topic, try doing some basic background research. Look up your topic in an encyclopedia (or even Wikipedia) and write down important words and phrases. If your reference source lists citations, you'll probably want to follow them up. Sources like encyclopedias are a good way to start your research, but you want to use them as a tool to get to other information, not as your final research.

Choosing Your Databases

Once you've got a topic and a strategy, you need to decide where to search for information. Some tools are better for finding specific types of information, so think about what type of information you want.

Library Search

Our Library Search finds books, multimedia, and articles available from the library, either online or in the building. It can be a good place to start your research, but you'll get a lot of results!

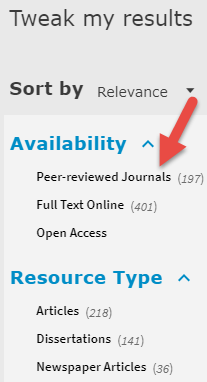

Remember that you can use the limiters on the right side of any results screen to narrow down your search. For example, if you know you want a peer-reviewed journal article, limit your search to "Peer-reviewed journals". You can also limit your results by resource type (books, articles, videos, and more), creation date, and other useful criteria. Be sure to click "See more" if you don't see the resource type you're looking for.

General Databases

If you're looking for peer-reviewed articles from scholarly journals, you might want to consider looking in database that contains articles from many disciplines. They're a great place to start if you're not as familiar with your topic or field. You may get more results than you need, but you'll get a sense of what's out there. General databases are also a great way to see what people in other disciplines are saying about your topic. Some good databases to start with are:

-

Academic Search UltimateAcademic Search Premier contains peer-reviewed journal articles. Almost every subject is included.

-

Academic OneFileAcademic OneFile contains citations and is a source for peer-reviewed, full-text articles from leading journals, covering the physical and social sciences, technology, medicine, engineering, the arts, technology, literature, and many other subjects.

-

JSTORJSTOR contains peer-reviewed journal articles. MyJSTOR accounts allow you to read up to six articles a month online for free (not subscribed to by the college) and save your citations to My Workspace.

Subject Databases

If you're looking for peer-reviewed articles or some specialized resources (datasets, statistics, etc) you'll probably want to be in a subject-specific database. As you learn more about a subject, you'll start to become familiar with related databases. If you're not sure which to use, you can check out our Subject Guides for some help.

Research Help

- Ask a Librarian

- Email us at Reeves.Library@westminster-mo.edu

- Call us at (573) 592-5247

- Text us at (877) 355-4542

- Text to chat with a librarian most hours of the day. (877) 355-4542

Search all Resources with Discovery

Search Credo for Reference Books

Subject / Content Guides-A-Z

Additional Guides

Additional Topics of Interest

Westminster College

Contact Us

Off campus?

Choose your database,

Sign in with your email account

and campus password.

Looking for a Specific Item

If you know what you’re looking for, finding it is usually pretty easy. Many times, all you need to do is enter the title or part of the title (preferably in quotes) in the Library Search box on the Library homepage. If the title isn’t very distinctive (“Introduction to Psychology”), you might also want to include the author.When searching for a book, you may find that reviews of the book turn up in your results, sometimes higher in the list than the book itself. You can limit your results to just books by clicking on “Books” under “Resource Types.” You may need to click on "Show More" to see the selection for books.

More information on Databases and Search Tips.

If you're still not finding the item you need, it's probably time to ask for Help.

You Need Sources on a Given Subject

When you start researching a topic, you'll want to think about the concepts that are involved. In addition to the words that are part of your topic, think about other ways you could express them, or other related ideas.

Let’s say you’re researching reforestation projects in tropical rain forests. You could do a search like this:

If you’d rather not worry about all those ANDs, ORs, and parentheses, you can use the advanced search and enter your terms on multiple lines. Advanced search also gives you options for limiting by material type, language, and date.

Narrowing Your Results

Library Search searches a LOT of data sources, so it will often return a huge number of results. Fortunately, it provides simple tools for limiting your results.

One of the most useful limiters is Source Type. If you’re looking for a book, you can limit to just books as described above. Notice that only the top source types are shown on your results page, so you may have to click “Show More” to see the type you’re looking for.

A handy shortcut for academic research is to limit your search by selecting just peer-reviewed journal articles.

Another useful limiter is “Publication Date.” For instance, if we wanted contemporary reviews of a movie, we might limit to our search to a creation date in the 1980s.

Still Need More?

Subject Headings

Sometimes you might find one or two items that are great for your topic, but can’t find any more. One way to address this situation is to use subject headings. Look at the subjects listed for one of your best sources and try adding these to your search.

Bibliographies

Another way to leverage a few good sources to find more sources is to examine their bibliographies. These can point you to important older research on the topic.

Other Databases

For most library searches, Library Search should be fairly effective. But sometimes you may find that your subject is not well-represented in the database (e.g., music) or you may just want to go deeper to see what else might be available. The Library's Databases page provides an alphabetical directory to all of our databases.

In Library Search, there should always be a link to get you to the full text if the source is available online. Most other library databases will include links that allow you to easily check to see if the Library has access to the article you're interested in.

Clicking on the link will open a new window with information about the Reeves Library's access to the article. If you're lucky, you'll see the full text of the article right away. If you're not so lucky, you'll need to send a request to Interlibrary Loan.

Which Search Tool When

- Library Search

Use to find relevant materials in databases, books, images, scores, and multimedia. Does not search all library databases.

- Library Databases

Use to do focused subject searching and retrieve highly relevant sources for your research.

- WorldCat

Use to find books that are available at libraries around the world.

- Subject Guides

Use to find the best databases and other information sources for academic majors and programs.

- Google Scholar

Use to locate scholarly materials on a topic

- Web search

Use to verify quick facts and find general websites.

Research Help

- Ask a Librarian

- Email us at Reeves.Library@westminster-mo.edu

- Call us at (573) 592-5247

- Text us at (877) 355-4542

- Text to chat with a librarian most hours of the day. (877) 355-4542

Search all Resources with Discovery

Search Credo for Reference Books

Subject / Content Guides-A-Z

Additional Guides

Additional Topics of Interest

Westminster College

Contact Us

Off campus?

Choose your database,

Sign in with your email account

and campus password.

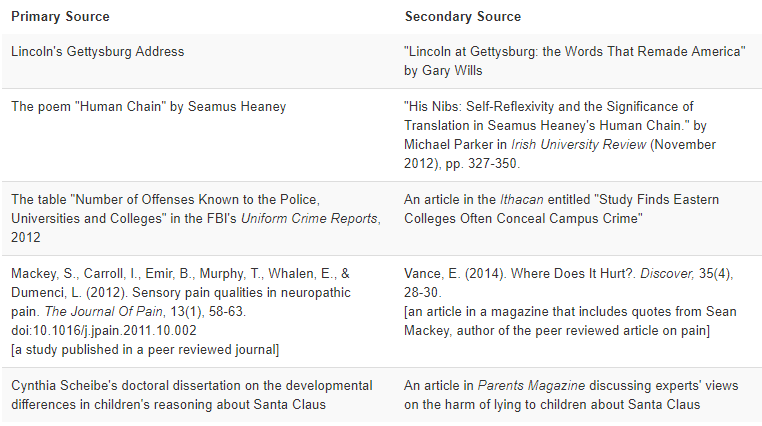

Primary vs. Secondary

For some research projects you may be required to use primary sources. How can you identify these?

Primary Sources

A primary source provides direct or firsthand evidence about an event, object, person, or work of art. Primary sources include historical and legal documents, eyewitness accounts, results of experiments, statistical data, pieces of creative writing, audio and video recordings, speeches, and art objects. Interviews, surveys, fieldwork, and Internet communications via email, blogs, listservs, and newsgroups are also primary sources. In the natural and social sciences, primary sources are often empirical studies—research where an experiment was performed or a direct observation was made. The results of empirical studies are typically found in scholarly articles or papers delivered at conferences. Primary Source Analysis tool (Hint click on Question mark for questions related to specific types of materials)

Additional Explanations and Examples of Primary Sources

Websites

-

American MemoryWritten and spoken words, sound recordings, still and moving images, prints, maps, and sheet music that document the American experience. From the collections of the Library of Congress and other institutions.

-

The American Presidency ProjectMajor publications of the U.S. Office of the President, including: public papers of the President, inaugural addresses, executive orders, radio addresses, party platforms, videos of debates, and popularity polling data. Developed by two political science professors at the University of California Santa Barbara.

-

Chronicling AmericaHistoric newspapers and select digitized newspaper pages from the National Digital Newspaper Program, a partnership between the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Library of Congress.

-

Digital Public Library of AmericaPhotographs, manuscripts, books, sounds, moving images, and more from libraries, archives, and museums around the United States. Search by format to locate Primary Sources.

-

David Runsey Map CollectionRare 18th and 19th century maps of North and South America, Asia, Africa, Europe, and Oceania.

-

Duke Collection of American Indian Oral HistoryOral histories collected from 1967-1972 from hundreds of Oklahoma Indians about all aspects of their lives.

-

Fed FlixVideo files from all aspects of U.S. history. Sponsored by the National Technical Information Service and the non-profit open government organization Public.Resource.Org

-

Indian Peoples of the Great Northern PlainsPhotographs, paintings, ledger drawings, documents, serigraphs, and stereographs from 1874 through the 1940's. From Montana State University, the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, and Little Big Horn College in Crow Agency, Montana.

-

Internet ArchivePermanent access to historical collections including texts, audio, and moving images.

-

LIFE Photo ArchiveImages from U.S. and world history from the 1750s to the 2000s.

-

LOC Prints & Photographs Online CatalogPhotographs, fine and popular prints and drawings, posters, and architectural and engineering drawings that document the history of the United States people. From the Library of Congress.

-

Making of AmericaPrimary sources in American social history primarily from the antebellum period through reconstruction. Strong in the subject areas of education, psychology, American history, sociology, religion, and science and technology. A collaborative effort of the University of Michigan and Cornell University.

-

New York Public Library Digital CollectionsImages from the The New York Public Library's collections, including illuminated manuscripts, historical maps, vintage posters, rare prints, photographs and more.

-

World Digital LibraryPrimary materials from countries and cultures around the world. Available in multilingual formats. Operated by UNESCO and the United States Library of Congress.

Library of Congress: Teachers Resources

History Matters: Making Sense of Evidence

The National Archives: DocsTeach

The National Archives Teacher’s Resources: Special Topics and Tools

Links to databases with some Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources describe, discuss, interpret, comment upon, analyze, evaluate, summarize, and process primary sources. Secondary source materials can be articles in newspapers or popular magazines, book or movie reviews, or articles found in scholarly journals that discuss or evaluate someone else's original research.

Serials

Journals, magazines, and newspapers are serial publications that are published on an ongoing basis.

Many scholarly journals in the sciences and social sciences include primary source articles where the authors report on research they have undertaken. Consequently, these papers may use the first person ("We observed…"). These articles usually follow a standard format with sections like "Methods," "Results," and "Conclusion."

In the humanities, age is an important factor in determining whether an article is a primary or secondary source. A recently-published journal or newspaper article on the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case would be read as a secondary source, because the author is interpreting an historical event. An article on the case that was published in 1955 could be read as a primary source that reveals how writers were interpreting the decision immediately after it was handed down.

Serials may also include book reviews, editorials, and review articles. Review articles summarize research on a particular topic, but they do not present any new findings; therefore, they are considered secondary sources. Their bibliographies, however, can be used to identify primary sources.

Books

Most books are secondary sources, where authors reference primary source materials and add their own analysis. "Lincoln at Gettysburg: the Words that Remade America" by Gary Wills is about Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. If you are researching Abraham Lincoln, this book would be a secondary source because Wills is offering his views about Lincoln and the Gettysburg Address.

Books can also function as primary sources. For example, Abraham Lincoln's letters, speeches, or autobiography would be primary sources. To locate primary sources in the library catalog, do a keyword search and include "sources" in your search. The search results for "Abraham Lincoln" and "Sources" would include include "The Civil War: the First Year Told By Those Who Lived It", a book that includes letters written by Abraham Lincoln.

Visual and Audio Materials

Visual materials such as maps, photographs, prints, graphic arts, and original art forms can provide insights into how people viewed and/or were viewed the world in which they existed.

Films, videos, TV programs, and digital recordings can be primary sources. Documentaries, feature films, and TV news broadcasts can provide insights into the fantasies, biases, political attitudes, and material culture of the times in which they were created. Radio broadcast recordings, oral histories, and the recorded music of a particular era can also serve as primary source material.

Archival Material

Manuscripts and archives are primary sources, including business and personal correspondence, diaries and journals, legal and financial documents, photographs, maps, architectural drawings, objects, oral histories, computer tapes, and video and audio cassettes. Some archival materials are published and available in print or online.

Government Documents

Government documents provide evidence of activities, functions, and policies at all government levels. For research that relates to the workings of government, government documents are primary sources.

These documents include hearings and debates of legislative bodies; the official text of laws, regulations and treaties; records of government expenditures and finances; and statistical compilations of economic, demographic, and scientific data.

Tertiary Sources

Tertiary sources contain information that has been compiled from primary and secondary sources. Tertiary sources include almanacs, chronologies, dictionaries and encyclopedias, directories, guidebooks, indexes, abstracts, manuals, and textbooks.

Research Help

- Ask a Librarian

- Email us at Reeves.Library@westminster-mo.edu

- Call us at (573) 592-5247

- Text us at (877) 355-4542

- Text to chat with a librarian most hours of the day. (877) 355-4542

Search all Resources with Discovery

Search Credo for Reference Books

Subject / Content Guides-A-Z

Additional Guides

Additional Topics of Interest

Westminster College

Contact Us

Off campus?

Choose your database,

Sign in with your email account

and campus password.

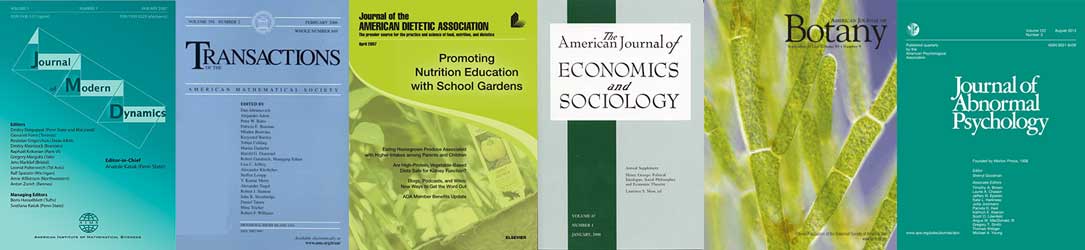

Scholarly Journals

For research assignments, a professor may require that you use "scholarly" or "peer reviewed" journals. These are journals whose purpose is to disseminate new findings, results of studies, theories, etc.

Scholarly journals are written and edited by professors and researchers. Before publication, articles are reviewed by other researchers in the field of interest, hence the name "peer reviewed."

Many Library databases allow you to limit your search results to peer reviewed articles.

Appearance and Format

- Plain covers that vary little from issue to issue

- "Journal," "Transactions," "Proceedings," or "Quarterly" commonly appear in title

- Articles include sections such as: abstract, keywords, literature review, methodology, results, conclusion

- Articles may have charts or graphs

- Advertising limited to books and meetings

- Pages numbered consecutively throughout a volume (rather than starting again at "1" with each issue)

Frequency of Publication

- Monthly or quarterly

Authors & Editors

-

Authors are scholars writing about their own research. They are usually affiliated with a college, university, or research institue and that affiliation will be stated

-

Articles are reviewed by a board of experts ("peer reviewed")

Readership & Language

- Aimed at practitioners in a particular field of study

- Language is often intensely academic, using the jargon of the field

Documentation

- Sources are always cited using footnotes or parenthetical references

- "Works cited" section at end of articles

Trade or Professional Journals

Trade journals are written for "insiders" in a particular industry. Some may look similar to popular journals, but they aren't intended for a general readership.

Appearance and Format

- May have a bright, glossy cover that varies from issue to issue

- Title usually includes the name of the industry or profession

- Articles short to medium length—rarely longer than a few pages

- Article types include industry news, opinion, practical advice, product reviews

- Often have illustrations, charts, or graphs

- Advertising for products aimed at industry professionals

Frequency of Publication

- Usually monthly; sometimes weekly

Authors & Editors

-

Authors are usually specialists in the field, sometimes journalists

Readership & Language

- Aimed at practitioners in a particular industry or profession

- Articles use jargon of the industry

Documentation

- May or may not include citations

Popular Journals

Popular publications include news, feature stories, opinion/editorial pieces, etc. They are meant to inform and entertain.

Popular publications include news, feature stories, opinion/editorial pieces, etc. They are meant to inform and entertain.

Appearance & Format

-

Usually a bright, glossy, eye-catching cover

-

Articles short to medium length

-

Lots of advertising for general consumer products

-

Colorful photos and illustrations

Frequency of Publication

- Weekly or monthly

Authors & Editors

-

Authors are magazine staff members or free-lance writers

-

No editorial peer-review process

Readership & Language

-

Written to appeal to a broad segment of the population.

-

Articles written for a general audience; fairly jargon-free

Documentation

- Citations and bibliographies are rare

Research Help

- Ask a Librarian

- Email us at Reeves.Library@westminster-mo.edu

- Call us at (573) 592-5247

- Text us at (877) 355-4542

- Text to chat with a librarian most hours of the day. (877) 355-4542

Search all Resources with Discovery

Search Credo for Reference Books

Subject / Content Guides-A-Z

Additional Guides

Additional Topics of Interest

Westminster College

Contact Us

Off campus?

Choose your database,

Sign in with your email account

and campus password.

Critical Thinking

As the amount of published information continues to grow exponentially, it is important to think critically and evaluate your sources. Content is published by individuals, organizations, businesses, governments, and countries. Note that there is no automatic formal review of some published content. While the content on the Reeves' Library website and in our print, media, and online collections has been selected by professional librarians, other content may be published and/or posted on the Web by non-experts. The ability to evaluate the information you find is a key critical thinking skill.

We recommend using the ACCORD METHOD (Agenda, Credentials, Citations, Oversight, Relevance, Date) to determine if information is appropriate for a research project. The ACCORD Checklist helps you evaluate information.

ACCORD checklist

Agenda

Information is published for various reasons - as advertising, entertainment, public service, sharing of ideas/opinions, and serving as a forum for scholarly ideas and research. It is important to determine why and for whom the information was published.

Factors to consider in reviewing the agenda of a resource:

-

For whom was the information published (or website made) and why? Is it to inform, sell, entertain, or advance an opinion?

-

For websites, is advertising included?

-

Is the purpose of the information stated and clear?

-

Are there personal, political, religious, or cultural biases presented?

Credentials

It is important to determine an author's identity in order to establish the reliability of the information presented.

Factors to consider in reviewing the credentials of an author:

-

Who is the author of the information?

-

Are the author's credentials and affiliations listed?

-

Is contact information provided for an individual author or an organization?

-

What are the qualifications of the author or group that published the information?

-

For websites, what is the domain name in the URL? For example: .com, .edu, .gov, .net, .mil, .org, or a personal website such as rachaelray.com

-

Does an organization appear to sponsor the information?

Citations

A review of the list of any sources cited is an important step in evaluating a resource.

Factors to consider in reviewing the citations listed by a resource:

-

Does the author cite the works of others?

-

Are the sources listed in the bibliography or included links related to the focus of the research/purpose of the site?

-

What kinds of sources are linked/listed?

-

For online documents, are links still current, or have they become dead ends? Note: The quality of Web pages linked to an original Web page may vary; therefore, you must always evaluate each Web site independently.

Oversight

Oversight in publishing involves a review/editing process - authors submit book manuscripts and/or articles to editors who review the content or forward it to experts in the field for review. Because the reviewers specialize in the same scholarly area as the author, they are considered the author’s peers. Editors and reviewers carefully evaluate the quality of the submitted manuscript, check for accuracy and assess the validity of the research methodology and procedures. If appropriate, they suggest revisions. If a book contains entries by multiple authors there may be a list of expert reviewers who were responsible for assessing individual entries.

Factors to consider in reviewing the oversight of a resource:

-

Has the information been reviewed or refereed?

-

Is the journal in which you found an article or the book published or sponsored by a professional scholarly society, professional association, or college/university academic department or scholarly press? (To verify, check the journal or publisher's website).

Relevance

How pertinent is the data in relation to your topic? This involves a review of the intended audience and how the information relates to the specific topic.

Factors to consider in reviewing the relevance of a resource:

-

Does the information relate to or answer your research question?

-

Does the information meet the requirements of your assignment? (primary or secondary source? popular or scholarly source?)

-

Is the information too technical or too basic for your needs? Is the intended audience for the material the expert or the non-expert?

-

Is the information presented appropriate in terms of depth and breadth?

Date

The currency of information is essential for some types of research and less so for others. Historical information that reflects people and events that have occurred in the past is relevant to historical research in many fields. In other fields such as health care, legislation, and finance, current information is used in research.

Factors to consider in reviewing the date of a resource:

-

When was the information published or last updated?

-

Have newer articles been published on your topic?

-

Are links or references to other sources up to date? Do the links work?

-

Is your topic in an area that changes rapidly or will older sources work as well?

Check the bottom of a webpage for the publication date, copyright date, or date last updated information. The copyright information for physical materials is listed in the catalog record and/or the bibliographic information.

Research Help

- Ask a Librarian

- Email us at Reeves.Library@westminster-mo.edu

- Call us at (573) 592-5247

- Text us at (877) 355-4542

- Text to chat with a librarian most hours of the day. (877) 355-4542

Search all Resources with Discovery

Search Credo for Reference Books

Subject / Content Guides-A-Z

Additional Guides

Additional Topics of Interest

Westminster College

Contact Us

Off campus?

Choose your database,

Sign in with your email account

and campus password.

Why Cite?

Citation is the practice of providing information about the sources you have used in your writing. This allows readers to trace ideas back to their original sources and gives credit to the original author.

Citation acknowledges any source that has directly influenced your language, ideas, or arguments. You should cite not only what you quote, but also what you paraphrase.

If you don't cite, you may be guilty of plagiarism.

Elements of a Citation

While the exact parts of a citation vary from one source type to the next, the most common elements address the questions who, what, when, and where.

Who

This is the name of the person (author, composer, artist) who is responsible for the work being cited. More rarely, it may be an institution rather than an individual, as in many government documents.

What

The title of the work

When

The date of the item being cited. Usually, only the year is required, but if you have more specific information, you can include that as well.

Where

Where can someone who is interested in this source find it? This information may include one or more of the following:

- Publication title (with volume, number, and page numbers)

- URL - for example, http://www.cnn.com/2017/04/07/politics/xi-trump-summit-syria/

- DOI (digital object identifier) - for example, 10.1016/j.nut.2015.05.021

When to Cite

A common misconception is that you only need to cite when using a direct quote from the source. In fact, you need to cite whether you directly quote a source or paraphrase it. It's about the idea, not just the expression. More details about citation and paraphrasing can be found in the plagiarism page of Research 101.

In-Text Citations and Reference Lists

The citation process involves two parts.

1. The reference list (aka bibliography). This lists the complete details of every item you cite. It is located at the end of your paper.

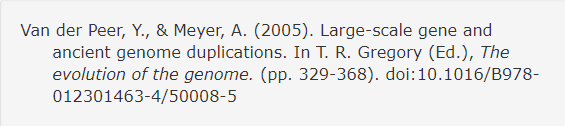

A full APA citation for an article might look like this:

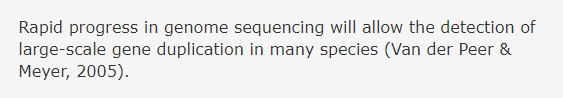

2. In-text citations. These are mini-citations that occur within the body of your paper, either as parenthetical notes or as footnotes at the bottom of the page. These give a shorter form of the citation. Interested readers can refer to your reference list for complete details.

The in-text citation for the paper listed above might look like this:

Citation Styles

Many different organizations and publications have developed rules for how sources should be cited. For undergraduate work, APA, MLA, and Chicago are the most used. Make sure that within a given assignment you follow the rules of the style preferred by your instructor. If your instructor just says "be consistent," pick one of the common styles to use. For information on specific styles, see our citation styles page.

Citation Managers

Writing citations and bibliographies can be tedious and time-consuming tasks. Luckily, there are some great free tools that will create them for you. Such tools will let you collect a set of sources and then drop them into your paper as you type. They will also let you automatically convert from one citation style to another. We recommend using Zotero.

Research Help

- Ask a Librarian

- Email us at Reeves.Library@westminster-mo.edu

- Call us at (573) 592-5247

- Text us at (877) 355-4542

- Text to chat with a librarian most hours of the day. (877) 355-4542

Search all Resources with Discovery

Search Credo for Reference Books

Subject / Content Guides-A-Z

Additional Guides

Additional Topics of Interest

Westminster College

Contact Us

Off campus?

Choose your database,

Sign in with your email account

and campus password.

What is Plagiarism?

Presenting someone else's words or ideas as your own is stealing, and in student work it also defrauds the instructor who grades it and your classmates who are judged on their own merits.

Plagiarism covers a wide range of theft. It is not limited to books and articles, but includes music, lectures, websites, and materials in all media and formats. Whether you are working on a paper or a homework assignment, developing a presentation or a website, it is important to credit your sources. Most cases of plagiarism are intentional, but even if you don't deliberately steal from someone else's work, you are answerable for careless thefts. When in doubt—cite!

Westminster College defines plagiarism as violating the Honor Code. More information can be found in the Westminster College Student Handbook by searching Honor Code or Plagiarism.

"Is it Plagiarism yet?"

Understanding and Preventing Plagiarism

How to maintain academic integrity by avoiding the pitfalls of plagiarism.

PaperRater.com

A free resource for analyzing documents immediately, in real-time. In-depth analysis is provided to help improve grammar, writing, readability, word choice, style and detect plagiarism.

Common Knowledge

Not all information requires requires citation. Factual information that is “common knowledge”—what your audience can be assumed to know—need not be cited. One simple test of common knowledge is to consult reference works to see if the information is widely reported and undisputed. Keep in mind, however, that common knowledge can change with context. Whereas a principle of physics would need to be cited in an undergraduate paper, the citation might be omitted from a paper presented at a scientific conference.

Quotation

The easiest way to avoid plagiarism is to quote a source word-for-word and set it off in quotation marks. Most citation styles follow a direct quotation with a brief, in-text citation pointing to the full citation in your end notes. Others follow a quotation with a superscript number corresponding to a numbered citation at the bottom of the page or in your end notes.

While direct quotations are a safe way to avoid plagiarism, they should not be too long or pepper your paper. Use them only if they provide a memorable phrase or well-formulated idea.

Paraphrasing

Paraphrasing is the act, perhaps the art, of rewriting a piece of text in your own words. But it is unacceptable simply to reword, rearrange or abbreviate a text and claim that this makes you the sole author. Plagiarism applies not only to words but also ideas, so paraphrasing a source does not make it your intellectual property. You must still provide in-text citations and full end notes for sources from which you have lifted observations or lines of argument—even in the absence of direct quotation.

Citing

There are dozens of citation styles, some of which are specific to a discipline or even a publisher. At Westminster College, there is no one style used by all professors. The most widely used are MLA (Humanities), APA (Social Sciences), and Chicago (including a variation known as Turabian). Always check with your instructor to see which citation style is required.

Citing is important not only because it avoids the act of plagiarism, but also because it acknowledges those who have contributed to your work, showcases the breadth and depth of your research, and serves as a road-map to readers who wish to consult your sources for themselves. Citing demonstrates that you are participating in and contributing to an ongoing dialogue on your topic. It is more than just a safeguard of intellectual property; it is an affirmation of civility, openness, and honesty.

See our Citation page for more information.

Research Help

- Ask a Librarian

- Email us at Reeves.Library@westminster-mo.edu

- Call us at (573) 592-5247

- Text us at (877) 355-4542

- Text to chat with a librarian most hours of the day. (877) 355-4542

Search all Resources with Discovery

Search Credo for Reference Books

Subject / Content Guides-A-Z

Additional Guides

Additional Topics of Interest

Westminster College

Contact Us

Off campus?

Choose your database,

Sign in with your email account

and campus password.